(I'm sorry if this is exorbitantly long and potentially not on-topic, but I got real excited about it.)

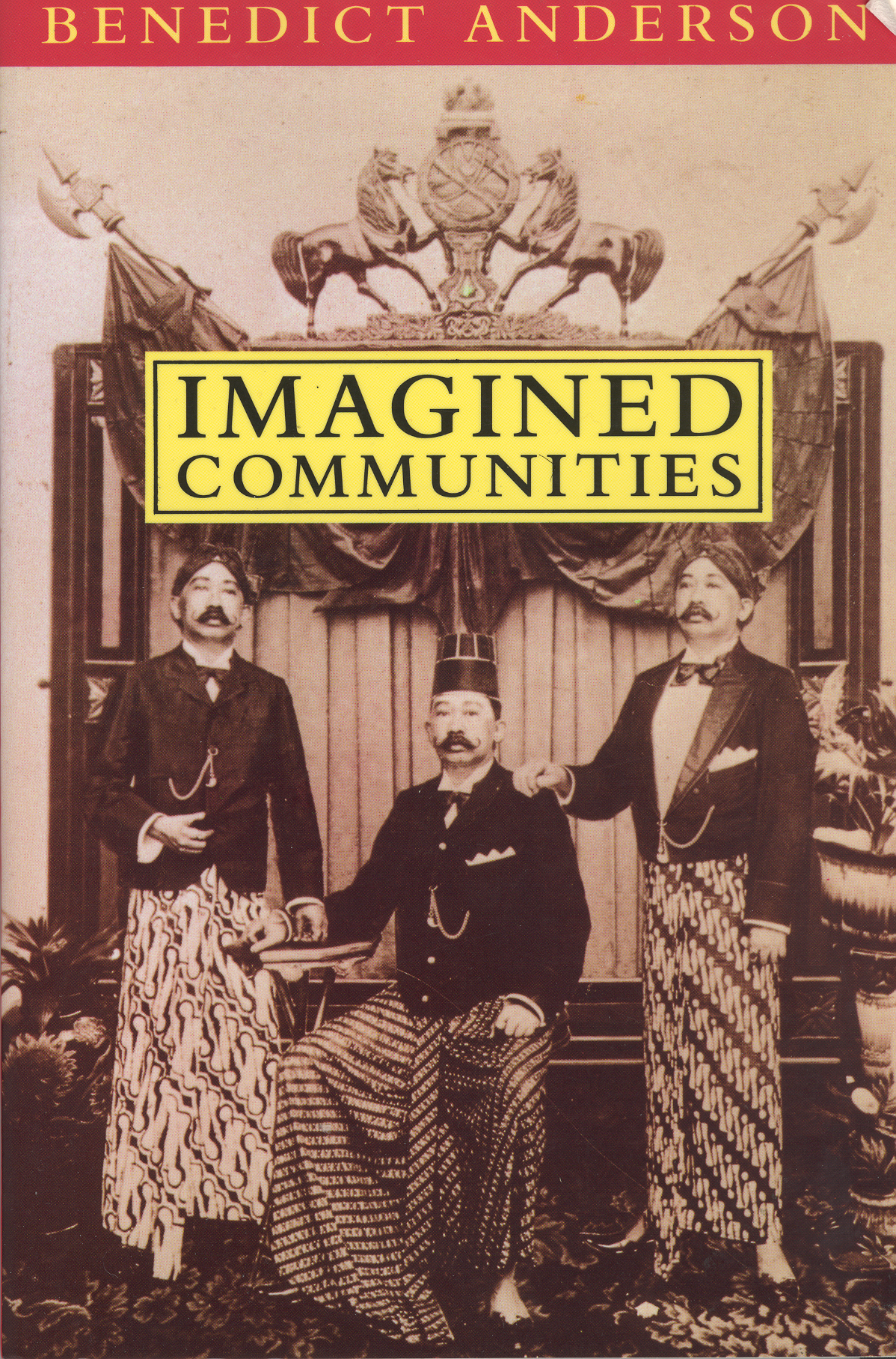

It might be the codeine-laden cough syrup I've been taking or my having finished the final chapter in

Imagined Communities, the icing on a cake I had a hard time swallowing, but I'm feeling a little feisty. As such I've been inspired by Kurt to go off-topic yet remain in context. Specifically, I would like to address (or, rather, raise) a different set of questions related to the "simultaneous" audience discussed in Anderson's book.

On page 26, Anderson writes,

An American will never meet, or even know the names of more than a handful of his 240,000,000-odd fellow-Americans. He has no idea of what they are up to at any one time. But he has complete confidence in their steady, anonymous, simultaneous activity.

And on page 33, he writes about news events that "disappear" in the papers over time:

if Mali disappears from the pages of The New York Times after two days of famine reportage, for months on end, readers do not for a moment imagine that Mali has disappeared or that famine has wiped out all its citizens.

Taking these two citations as a starting point, I would like to challenge Anderson on his assumption of simultaneous continuity. While it might have been true when Anderson first published this work, I think the issue of simultaneity has since become more complicated. Despite my dislike of this particular work, my challenge is not to argue his claim but to ask more from him than what he has given. In fact, from my

admittedly limited understanding of globalization and transnationalism, I'm not sure we (at least in "the developed West") care as much about "nation" as we seemingly did even a few decades ago, so I wonder, would this potential lack of nationalism have similar roots as this potential lack of simultaneity I'm going to introduce.

When I first read page 26, my initial marginal note was "reality?" I wrote this because I and, anecdotally, many people I know were struck by the disturbing potential of 1998's

The Truman Show. Now, film buffs and better-read folks than I can probably list dozens of fictional origins for the concept of illusory communities and life as an illusion. In fact, I can think of some that might count. But

The Truman Show was popular and I saw it earlier than I saw anything else that might count, so it's my example. In

The Truman Show, Jim Carrey's character thinks he's living in real life but in fact is living

his real life in a television show. He thinks the rest of the world's characters continue after they have left his view, but they don't, at least not in the way that he would expect. His is a fictitious case in which not only his community is imagined (or produced) but his understanding of the simultaneous, continuous existence of the rest of the world is also imagined (and only produced while he is awake and in a relevant scene). This, at least to me and many of those I know, was disturbing. We thought, what if we were Truman.

The following year came a similarly disturbing film with which I'm familiar, David Cronenberg's

eXistenZ. For those who don't know, it's a (fantastic) film about virtual reality video games in which the characters enter numerous levels of game and ultimately are left questioning reality. While Cronenberg has had other films, some of which have been adaptations of or were inspired by earlier works by other artists, its timeliness strikes me. (In the same year,

The Matrix came out and was far more popular and I'll take for granted you all know what it's about, but in short it also questions reality, although it does still offer some sort of "real" imagined community for those who have escaped.)

The year after that (2000) Maxis came out with

The Sims, a life simulator, much to the adoration of many video game fans and newcomers to the video game medium. Following that in 2004 was

The Sims 2, which took the first game even further into reality, with a full age cycle from birth through death of characters. And, again, while these were based on earlier simulators, their timeliness and the extent to which a.) they were popular, and b.) they were more true to the average American's lived experience (e.g. dealing with the dishes as opposed to managing a riot or war), I think makes a difference. In these three video games (

eXistenZ is the name of the video game in the eponymous film), there is a life that more or less assumes a simultaneity that the player recognizes as being illusory. After all, it's just a video game.

This brings me to my final example of imagined simultaneity in media, 2007's

The Nines, another (fabulous) film about multiple layers of reality. With this complexity of understanding reality, I'm not convinced that Anderson can make the statement that Americans unequivocably recognize that the rest of America keeps moving. Surely most do. But I think some of us (and I genuinely don't think we're psychologically damaged), at least those of us who have been confronted with the problem of an assumed reality, can't necessarily buy into (100%) the idea that the rest of the world keeps ticking in empty, homogeneous, continued time. I assume that you all are currently at home or in class or doing something, while I'm coughing away and typing in my living room. But deep in the back of my mind, because of these fictions I've consumed (and

this relevant New York Times article) I think that there is a .0001% chance that you all

might be in hibernation mode. I mean, I could be egomaniacal, but I think it's just postmodern anxiety.

So all of this rambling brings up some questions for me related to the first Anderson passage:

- 1.) Is there in fact much of an opinion out there regarding reality versus assumed reality that would caution an assumed simultaneity?

- 2.) If so, what are its roots and how might these be related to a dissolution of nationalist concerns in the face of transnationalist, globalist, or simply international concerns?

- 3.) As cyber communities (forums, multiplayer games, especially those like Second Life, even blogs) and virtual reality experiences proliferate, how might homogeneous time and simultaneous existence change?

- And to go even further science-nerdy than I have (and will in the post-script), 4.) How might something like infinite parallel universes (according to a 2005 Scientific American I read it's no longer a crackpot idea) tie in to the concept of homogenous time?

My reason for bringing up the second passage in the book is meant to be a little more light-hearted. I don't know about you but I know a great many people who would, if not assume that Mali had been eradicated by a famine, forget that Mali even existed if it wasn't mentioned with some regularity. Is that a more recent occurrence? A result of poor education standards? Previously, we didn't know certain countries existed, but now that we do and are

so constantly "in the know," it seems so easy to forget. Or maybe we never really remember but are just constantly told/reminded? (And did I miss this part of "Memory and Forgetting?")

==

The Post-Script:

And speaking of simultaneous experiences and insecure realities, did anyone hear about the CERN experiment with the Large Hadron Collider?

Stage 1 was successful, but I'm slightly concerned. Shouldn't we get to vote on whether we think it's a worthy endeavor (or a good use of resources) to potentially create black holes in Switzerland?